Since developing a system for phyloreferencing based on nodes in a particular phylogeny earlier this year, we’ve been working on extending it to support node- and branch-based definitions — if you know how to read pytest and TAP output, you can see this system correctly resolving most currently curated phyloreferences on Travis CI! Before those phyloreferences are ready for a proper release, however, we need to create a more flexible system for resolving phyloreferences by matching them with nodes in any phylogeny.

Annotating nodes on a phylogeny. Nodes on a phylogeny may be identified to a specimen or a taxon, whether at the species rank or higher, and may also be associated with morphological or molecular character data. In the Comparative Data Analysis Ontology (CDAO, described in Prosdocimi et al., 20091), this connection goes through an intermediate entity called a Taxonomic Unit (or TU), which CDAO defines as “a unit of analysis that may be tied to a node in a tree and to a row in a character matrix”. It therefore combines the commonly used but vaguely defined concept of an operational taxonomic unit with the less often used concept of a hypothetical taxonomic unit. A Node can be associated with a taxonomic unit through the represents_TU property, which in turn can be linked to an external taxonomic resource through the has_External_Reference property. External taxonomic resources may be drawn from the NCBITaxon ontology (an ontology of taxonomic names from the NCBI Taxonomy) or lineage-specific taxonomy ontologies such as the Vertebrate Taxonomy Ontology.

While these ontologies allow us to refer to entire taxa, we can also craft OWL expressions to refer to a part of a taxon. This may be done by using the part_of relation, as in General Class Inclusion axioms in Uberon. Mungall et al., 20122 provide the following example:

uberon:parathyroid_gland and part_of some ncbitaxon:Xenopus

SubClassOf develops_from some uberon:pharyngeal_arch_3

Some properties make it clear that they may only apply to a part of the taxon. This approach is taken by the Gene Ontology, which uses taxonomic constraints to specify that certain genes and processes are found “only in taxon some X” or “never in taxon some Y”, indicating that the property applies to some but not necessarily all instances (i.e. members) of that taxon. Deegan et al., 20103 have more details on taxonomic constraints.

Let’s work through an example of linking a node in a phylogeny with a taxonomic unit: when viewing a list of taxa for TreeBASE tree #4419 (found in study #1269), we find a terminal node labeled “Rana zweifelii”, which TreeBASE has identified to NCBI Taxon #299667. The Vertebrate Taxonomy Ontology identifies this taxon as VTO_0002750. We could model this node as:

_:Node1 a cdao:Node;

rdfs:label "Rana zweifelii";

cdao:represents_TU [

a cdao:TU;

cdao:has_External_Reference <http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/VTO_0002750>

].

(Note that I use human-readable names constructed from the term label, such as “cdao:represents_TU”, in place of the actual term identifier, which in this case is obo:CDAO_0000187).

This phylogeny was published in Hillis and Wilcox, 20054, who provide some additional information about the specimen this node is based upon. In table 1, we learn that it has a specimen identifier of “KU 195310”, that it was collected in “Mexico: Oaxaca: 1.6 mi S Cuyotepej”, and that the sequence information used in this analysis for this node has been accessioned as GenBank AY779219. It also reveals an error in the node label: the correct taxonomic name is Rana zweifeli, not Rana zweifelii (note the extra ‘i’). While I could not find an example of taxonomic names being stored in CDAO trees outside of a label, Prosdocimi et al., 20091 give an example for the case of annotating branches with character state transitions: they create the class EdgeTransition as a subclass of cdao:EdgeAnnotation, and use properties (cdao:has_Left_State and cdao:has_Right_State) to charactize the EdgeAnnotation instance that represents the state transition. Following this pattern, we could create custom classes that extend cdao:TUAnnotation to provide taxon name and specimen annotations, as follows:

_:TaxonNameAnnotation a owl:Class;

rdfs:subClassOf cdao:TUAnnotation.

_:SpecimenIdentifierAnnotation a owl:Class;

rdfs:subClassOf cdao:TUAnnotation.

_:Node1 a cdao:Node;

rdfs:label "Rana zweifelii";

cdao:represents_TU [

a cdao:TU;

cdao:has_External_Reference <http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/VTO_0002750>;

cdao:has_Annotation [

a _:TaxonNameAnnotation;

cdao:has_Value "Rana zweifeli Hillis, Frost and Webb 1984"

];

cdao:has_Annotation [

a _:SpecimenIdentifierAnnotation;

cdao:has_Value "KU 195310"

]

].

This class-based approach has certain advantages: for instance, we could create an ObservationAnnotation class with subclasses for photographs, preserved specimens or DNA collected from the environment, which might facilitate integration of different types of biodiversity data. However, this requires a lot of work upfront to define the classes we need and specify the values they could hold. Instead, we could use a property-based approach, in which we apply properties directly to the taxonomic units. This would allow us to build on the Darwin Core5 RDF vocabulary and the Darwin-SW OWL ontology6. Although the normative Darwin Core is not axiomatized using OWL (and thus properties are not axiomatically distinguishable as data or object properties), we could either declare the necessary data property type axioms ourselves, or use the terms defined in the Biological Collections Ontology, including classes such as PreservedSpecimen and properties such as catalogNumber.

We can use two other resources to further improve our description. The Nomen ontology (still in development) allows us to record that this scientific name is a name defined under the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. While no canonical URI is available for this specimen, we can look it up on VertNet and use its URI to identify it there. This information can be modeled as:

_:Node1 a cdao:Node;

rdfs:label "Rana zweifelii";

cdao:represents_TU [

a cdao:TU, dwc:Taxon, nomen:ICZN_name;

dwc:scientificName "Rana zweifeli Hillis, Frost and Webb 1984";

dwc:genus "Rana";

dwc:specificEpithet "zweifeli";

dwc:scientificNameAuthorship "Hillis, Frost and Webb 1984";

cdao:has_External_Reference <http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/VTO_0002750>

];

cdao:represents_TU [

a cdao:TU, dwc:PreservedSpecimen;

dwc:institutionCode "KU";

dwc:catalogNumber "195310";

dwc:locality "Mexico: Oaxaca: 1.6 mi S Cuyotepej"

cdao:has_External_Reference <http://portal.vertnet.org/o/ku/kuh?id=be1b5c81-b069-11e3-8cfe-90b11c41863e>

]

This model simplifies some complex ideas – such as the taxonomic identification of the phylogeny node – in order to focus on the minimal semantics we need for phyloreferencing. However, a few outstanding questions remain:

-

Can a taxon also be a scientific name? Arguably, no: a taxon is associated with a scientific name through original description or through subsequent taxonomic or nomenclatural changes. However, Darwin Core associates scientific name properties directly with a

Taxon, and not with a separate “Scientific Name” class. Darwin-SW recognizes anIdentificationas assigning organisms or their derived tokens to a taxon, which is also not what a taxon-based Taxonomic Unit does in our model. To stay in line with the Darwin Core/Darwin-SW view, we follow their convention: entities that are both taxonomic units and scientific names can have all the properties of scientific names, such as their taxonomic status, their authorship or their intended taxonomic circumscription, any of which may be used to match it to a node. -

Where do nodes fit into the Darwin-SW ontology? I think they act as a

Token: they are derived from anOrganism, and are identified to a taxon through anIdentification. However, within phyloreferencing, we don’t care how the identification of the node took place or which actual organisms the node token is derived from – we only care which taxonomic units they represent and whether those taxonomic units consist of an entire taxon, a taxonomic concept, a collection of populations, a set of individuals or even a single individual. -

Where do taxonomic units fit into the Darwin-SW ontology? This term doesn’t map perfectly: taxa and taxonomic concepts are clearly a kind of

Taxon, but a specimen is arguably aToken, linked to a taxon through anIdentification. I would argue that these distinctions are unimportant for data modeling: for phyloreferencing, we allow anything that qualifies as a taxonomic unit, whether it refers to a whole taxon, a set of specimens or a single specimen. We can match a taxonomic unit to any other taxonomic unit given a sophisticated matching algorithm: for example, we can match a specimen to a taxonomic unit based on a scientific name if we know about the current taxonomic identification of the specimen. -

Can a node sensibly represent multiple taxonomic units? One downside to separating nodes from taxonomic units is that it becomes possible for a node to represent multiple taxonomic units. In the example above, I use this to associate a node with an ICZN name as well as a specimen, both with their own external references. This seems reasonable, but what if I associated a single node with multiple taxon names or multiple specimens? We currently elect to treat each taxonomic unit as representing the node independently of all the others, i.e. while we don’t actually imply that the two taxon names are synonymous, we do match the node with either taxon name. The Open-World Assumption leaves open the possibility that additional taxonomic units will be attached to an existing node: this will not create new entailments (i.e. logical inferences), but will affect how nodes can be matched. A node can therefore represent multiple taxonomic units in a way that is useful for phyloreferencing but without implying any relationships between those taxonomic units.

In a fully Linked Data world, we could include additional information about the specimen, as recorded by VertNet: it was collected on June 3, 1983, at 17.91 N and 97.68 W, and that it is stored as a physical specimen preserved in ethanol. We could also extract individual characters from the DNA sequence stored at GenBank AY779219, which we could associate with this taxonomic unit through the has_TU property. Modeling this is currently beyond the scope of our project, but these may be used to combine biodiversity data and phylogenetic relationships within the same model.

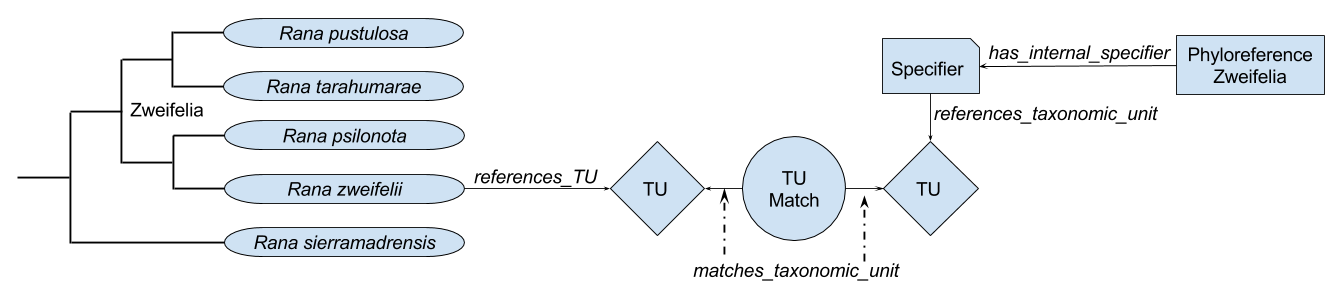

Matching phyloreference specifiers to nodes. Phyloreferences can be defined in terms of their specifiers: for example, a node-based phyloreference has multiple internal specifiers that must be included in the resolved clade. The portability of phyloreferences depend directly on how portably these specifiers can be matched against nodes on a phylogeny. To make this match, we can describe each specifier in terms of taxonomic units, and then match these taxonomic units against those that are represented by nodes in the phylogeny. A phyloreference could be defined in terms of its specifiers and their taxonomic units as follows7:

_:Zweifelia a phyloref:Phyloreference;

testcase:has_internal_specifier [

a testcase:InternalSpecifier;

testcase:references_taxonomic_unit [

a cdao:TU, dwc:Taxon, nomen:ScientificName;

dwc:scientificName "Rana zweifeli Hillis, Frost and Webb 1984"

]

];

testcase:has_internal_specifier [

a testcase:InternalSpecifier;

testcase:references_taxonomic_unit [

a cdao:TU, dwc:Taxon, nomen:ScientificName;

dwc:scientificName "Rana tarahumarae Boulenger 1917"

]

]

.

In these examples, I use exactly the same scientific name as I provided earlier; however, it is easy to imagine synonymous or misspelled names, different authorship information or other small differences between the taxonomic units referenced from the specifiers or represented by the nodes; this would make matching much trickier8. In this particular example, for example, the Amphibian Species of the World taxonomic checklist, version 6.0 treats Rana zweifeli as a junior synonym of Lithobates zweifeli. We can therefore imagine a specifier referencing the taxonomic unit R. zweifeli that should be matched with a node that represents the taxonomic unit L. zweifeli. While we can model this synonymy using Nomen ontology properties such as nomen:ICZN_synonym, doing so for all possible synonyms would add additional and likely unnecessary information to the OWL files we build, and would slow down the reasoner as it attempts to resolve phyloreferences.

Instead, we will begin by modeling taxonomic units in OWL, but then using other programming tools – such as SPARQL or an RDF library in Python or Java – to identify matching taxonomic units. This allows us to build arbitrarily complex matching rules, starting with the simplest ones we need to start matching phyloreferences and then building more complex ones that can incorporate sophisticated algorithms designed to accurately match potentially misspelled taxonomic names, such as Taxamatch. We can also call on taxonomic name resolution services, which contain databases of synonymous names that would allow us to accurately match synonyms. The provenance of these matches will be stored in a TUMatch object that matches one taxonomic unit with another. For example, given a specifier that references _:Taxonomic_Unit_1 and a node that represents _:Taxonomic_Unit_2, we could describe a match between these two entities as:

_:Taxonomic_Unit_Match_1 a testcase:TUMatch;

testcase:matches_taxonomic_unit _:Taxonomic_Unit_1;

testcase:matches_taxonomic_unit _:Taxonomic_Unit_2;

testcase:reason_for_match "Taxonomic units share binomial name 'Rana zweifeli'"

.

Once taxonomic units have been matched with each other, the node and specifier associated with them can be connected through by using OWL Property Chains. In this case, the property chain we need to follow can be defined in OWL Functional-Style Syntax as:

SubObjectPropertyOf(

ObjectPropertyChain(

testcase:references_taxonomic_unit

ObjectInverseOf(testcase:matches_taxonomic_unit)

testcase:matches_taxonomic_unit

ObjectInverseOf(cdao:represents_TU)

)

testcase:matches_node

)

With this new matching system in place, we see most phyloreferences resolving correctly, with two main remaining sources of errors: (1) specifiers failing to match because they use non-standard specimen identifiers (such as “Mishler 7/24/98(3), Queensland, Australia (uc)”), and (2) specifiers failing to match because their taxonomic units are entirely missing from the phylogeny being tested. Once these two common sources of error have been fixed, we can continue adding newer – and stranger! – phyloreferences to our test suite to see just how flexible and useful this model can be.

-

Prosdocimi et al. (2009) Initial Implementation of a Comparative Data Analysis Ontology, Evolutionary Bioinformatics 5:47-66. ↩ ↩2

-

Mungall et al. (2012) Uberon, an integrative multi-species anatomy ontology Genome Biology 13:R5. ↩

-

Deegan (née Clark) et al. (2010) Formalization of taxon-based constraints to detect inconsistencies in annotation and ontology development BMC Bioinformatics 11:530. ↩

-

Hillis and Wilcox (2005) Phylogeny of the New World true frogs (Rana), Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 34(2):299-314. ↩

-

Wieczorek et al. (2012) Darwin Core: An Evolving Community-Developed Biodiversity Data Standard, PLOS ONE. ↩

-

Baskauf and Webb (2016) Darwin-SW: Darwin Core-based terms for expressing biodiversity data as RDF, Semantic Web Journal 7(6):629-643. ↩

-

Note that terms in these OWL examples mix terms from two different ontologies. Some terms were defined in the

phyloref:ontology to refer to those terms defined in the proof-of-concept Phyloreferencing ontology, while other terms in thetestcase:namespace in the Testcase ontology are being developed as part of the test suite of phyloreferences we are currently building. As terms are found to be more broadly applicable than just in our test cases, they might be moved out of the Testcase ontology into the Phyloref ontology. ↩ -

For example, consider the 65 different permutations of names and authorships used by diatom taxonomists for Stephanodiscus minutulus. ↩