The Phyloreferencing (hereafter referred to as Phyloref) project team had our second face-to-face meeting on Oct 11 & 12, 2017. (The first one took place earlier this year in April.) This time we focused on Phyloref specifications, diversifying our driving use-cases, the curation workflow, concept taxonomy, and on creating a development roadmap with milestones, dates, and products.

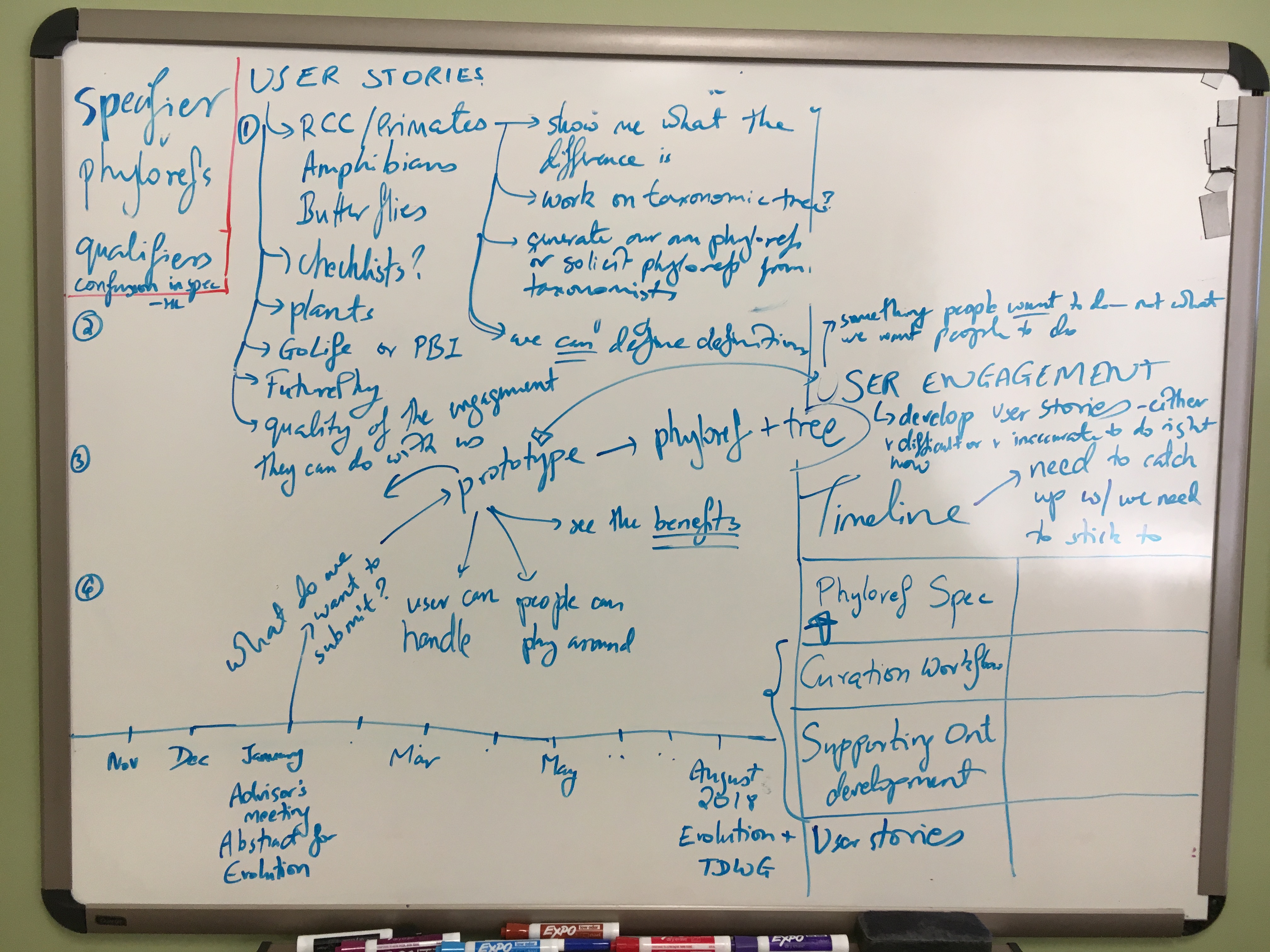

Diversifying our driving use-cases

Driving biological use-cases plays a critically important role in guiding our ongoing work on the Phyloref specification and the (inherently closely related) curation workflow, and in ultimately validating the results. Although several motivating use-cases are explained in the original proposal, they aren’t at a sufficiently concrete level, and they aren’t tied to stakeholders external to the project personnel. We brainstormed how we can best diversify our driving use-cases, in a way that bases them off of concrete user stories1, and that engages early on stakeholders external to our project. We looked at a number of clades that exemplify or magnify the challenges Phyloref is aiming to address, including primates, amphibians (e.g., Rana), butterflies and plants. This exercise resulted in re-committing ourselves to reach out to NSF GoLife projects, a task that Guanyang will spearhead. GoLife projects stand out in their utility to inform our work because they place special emphasis on generating data layers and integrating data with phylogenies, which aligns them well with one of the key objectives of our work, namely enabling and facilitating large-scale data integration based on phylogenetic knowledge. Guanyang will be working with Nico to contact GoLife project PIs to explain what we are doing and how opportunities for cross-project collaboration could look like.

Concept taxonomy

Concept-based taxonomic reconciliation methods have received increasing attention as a possible approach to capturing and reconciling the semantics of taxonomic concepts in a way that could be machine-accessible. To more thorougly explore and better understand the delineation between our work and concept taxonomy, Guanyang took us on an in-depth tour of concept-based taxonomic reconciliation methods, focusing on two approaches: concept taxonomy and Avibase. Concept taxonomy attempts to resolve ambiguities of taxonomic names by specifying the source of concept circumscription when a name is used. In a grant proposal by Nico Franz this is illustrated with an example of using concept taxonomy to reconcile taxonomic history of southeastern orchids in the genus complex Cleistes/Cleistesiopsis. Avibase, a taxonomic and biodiversity database for birds, also utilizes taxonomic concepts, but in a very different way. A more detailed juxtaposition of the two approaches is beyond the scope of this report, but will be forthcoming as a separate blog post.

Phyloref specification and phyloreference curation

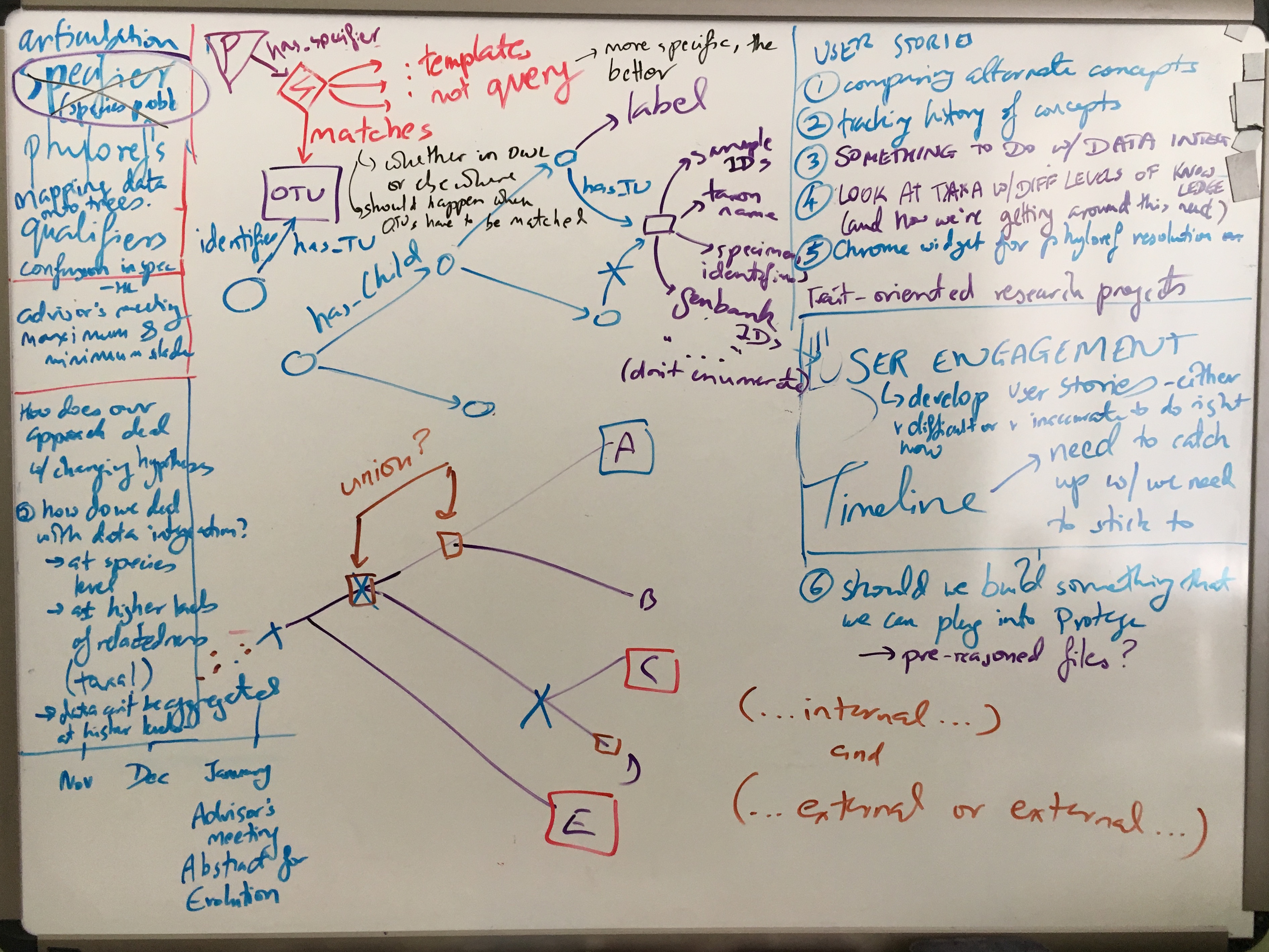

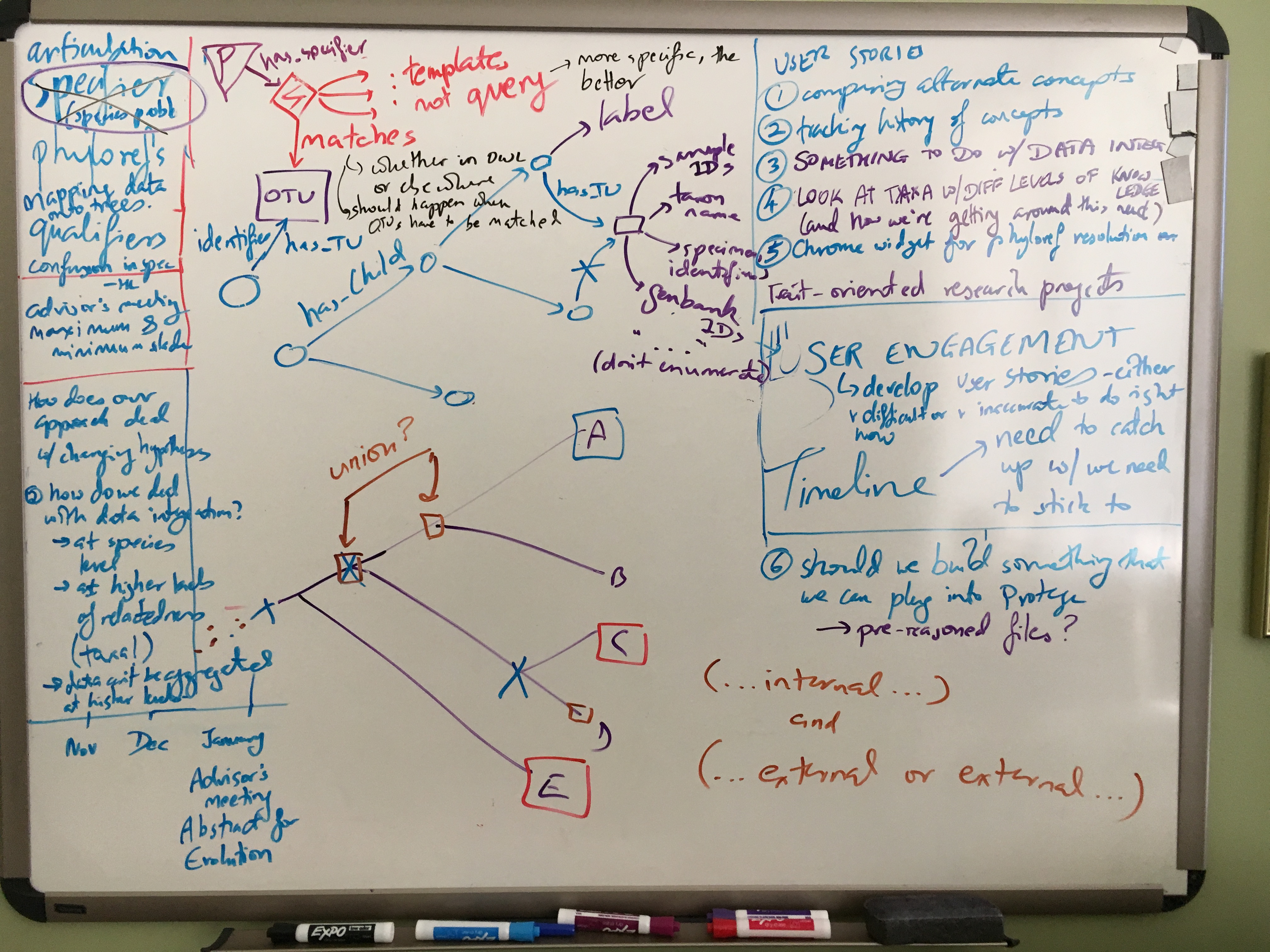

Most of the meeting was spent discussing Phyloref specifications and the curation workflow. In particular, two hairy issues were discussed at length: the role and semantics of qualifying clauses in nomenclatural phylogenetic clade definitions, and how best to model OTUs.

Specifiers in qualifying clauses

Specifiers in a phylogenetic clade definition normally identify the nodes that define the ancestor anchoring the clade, by having to be descended from or (for branch-based definitions) required to not be descended from the ancestor. However, sometimes published phylogenetic clade definitions include a qualifying clause. Such a clause acts in a way as a conditional self-destruction device. Specifiers appearing in a qualifying clause do not themselves take part in determining the common ancestor anchoring the clade. Instead, the clause serves as an enduring requirement, requiring, for example, that certain specifiers fall within the clade. If, for example, new data and resulting phylogenetic knowledge were to put the respective specifiers outside of the clade, the clade definition would then become invalid from the standpoint of phylogenetic nomenclature2.

From the Phyloref perspective, phyloreferences don’t become invalid or inapplicable. (As ontology terms, one might state axioms declaring them as obsolete, but that is quite different.) This raises therefore the question as to how best to represent, in the form of logic (OWL) axioms, the intent of the author who published the phylogenetic clade definition. We concluded that a phyloreference that in a given tree doesn’t “match” any nodes would correspond most closely with the nomenclatural case of a phylogenetic clade definition that becomes inapplicable when its qualifying clauses aren’t met anymore by the prevailing phylogenetic knowledge. How best to implement this in OWL will need to be investigated; so far only our OWL model for branch-based clade definitions (which work by exclusion) allows a phyloreference not to match, namely when a given phylogeny does not support the exclusion. One of the challenges here is due to a limitation of OWL, our chosen language for modeling data semantics, in that OWL lacks a notion of property chain length, and thus lacks property path length as an attribute that could be used in axioms. Although the benefits of using OWL, including its large supporting community and tool ecosystem, are strong, at some point the question of best suitable implementation context for phyloreferences may need revisiting. This issue also suggests that it is advisable to decouple the language in which phyloreference semantics are formally defined and modeled (OWL) from the one in which a machine reasoner might operate or be implemented.

Representing OTUs

What is an OTU and what kind of properties and property values can be used to identify it? OTU is a rather ambiguous term and interpreted in highly variable ways by different communities and domain experts. When modeling OTUs in an ontology, what kinds of ontological commitment do we have to make, and is it possible to avoid using the concept altogether? Matching OTUs is necessary to accomplish our stated objective of resolving phyloreferences against phylogenies, and because there is no universal standard for identifying OTUs, the options are many in terms of the kinds of things or entities that could be used in the wild to identify an OTU. It could be a taxonomic name, a sample ID, a specimen accession number, a Genbank accession number, etc. Given this wide variety, and to avoid ontological confusion3, we determined that explicitly modeling OTUs as a concept will need to be part of the Phyloref specification, even if perhaps as an addendum rather than within the core.

Timeline, milestones, MVP

In terms of timeline, and milestones precipitated by it, we discussed planning ahead for project-specific meetings and pertinent major conferences in the coming year. In the former category, our first Advisory Board meeting (to be held virtually) is currently targeted for February or March 2018. In the latter category, both the 2018 Evolution Meetings and the TDWG conference will take place in August 2018, about 1 week apart. We resolved to have a prototype, in the form of an MVP (Minimum Viable Product), as one of the major milestones to be accomplished in time for presentation at either meeting.

This prototype should have the following features.

- Reciprocal queries using a phylogeny or a phyloreference as an input. When a phylogeny is provided as an input, a query should generate a list of phyloreferences pertaining to that phylogeny. On the other hand, if a phyloreference is used as an input, the query should resolve to a node/clade on a phylogeny.

- Clear benefits to users, as motivated by the user stories we plan to elicit.

- Usable for biologist end-users.

The second and third points are quite self-explanatory. In summary, the prototype should be demonstrably useful, appealing and accessible to biologists.

Phyloreferences as products

Gaurav demonstrated using Protege to visualize phyloreference OWL files. Hilmar pointed out that these OWL files are themselves project outputs: they should be polished into clearly documented ontologies that any person familiar with OWL should be able to understand. Editing, testing and fixing the input JSON-LD files should also occur through a graphical user interface (GUI) — curators of phyloreferences should not be expected to edit JSON-LD files by hand, and a GUI could simplify the process of importing multiple phyloreferences from a single paper. This would help us expand our test suite quickly, and might form the basis of the prototype we’re aiming to develop next.

Development-focused exchange visit with Duke

Among the postdoc training and project coordination activities anticipated in the original grant proposal is an annual exchange visit of the postdocs in Nico’s lab with Hilmar’s group at Duke, to focus on ontology, reasoning, and software development issues, as well as to take advantage of knowledge exchange with the professional software developers in Hilmar’s team. We planned out a visit for Guanyang and Gaurav to Duke in December. If selected for the Phenoscape workshop, Guarav and Guanyang can combine the visit with the workshop.4

Ongoing issues left pending

We discussed several issues that have surfaced in our ongoing work, but which we had to leave unresolved pending further research and exploration. These include the following:

- Part of honing our outreach and research publishing is answering the question of how Phyloref differs from other taxonomic resolution/reconciliation approaches. How can we most succinctly articulate what Phyloref can do that other services cannot? Relatedly, how do we most persuasively communicate about what biologists need to do that we might be able to provide, in contrast to or better than other approaches or services?

- In light of some recent uncertainties about OWL-DL expressivity being capable of capturing all phyloreference definitions encountered in the wild, how do we best drive towards verifying that OWL remains the best formal logics language for implementing the machine-readable clade semantics part?

- Although phyloreferences are fully portable from one phylogeny to another in theory, what will limit this portability in practice, given that specifiers still need to be matched somehow?

- What does it mean for the concept of a clade as originally published if a phyloreference is applied to a phylogeny that has evolved from the one for which it was originally published? Can we create tests that flag and possibly visualize such changes?

-

A User Story has a formal role in software development. For our purposes, we use it in the sense of goals that a user wants to accomplish and why, and that currently can be accomplished either only in a way that is unsatisfactory in some important way, or not at all. ↩

-

Article 11.9 of the PhyloCode (version 4c) says that “phylogenetic definitions may include qualifying clauses specifying conditions under which the name cannot be applied to any clade”. Also, Article 6.5 states that an accepted name of a taxon cannot have been “rendered inapplicable by a qualifying clause in the context of a particular phylogenetic hypothesis.” ↩

-

As the Evolutionary Informatics Working Group at NESCent concluded many years ago, the use of “taxon” for both an OTU and for a class in Organismal Taxonomy is a cause of confusion. ↩

-

Both Gaurav and Guanyang were accepted to attend the Phenoscape workshop and this trip will take place in the early part of Dec. ↩